COLLECTION

CICATRICES

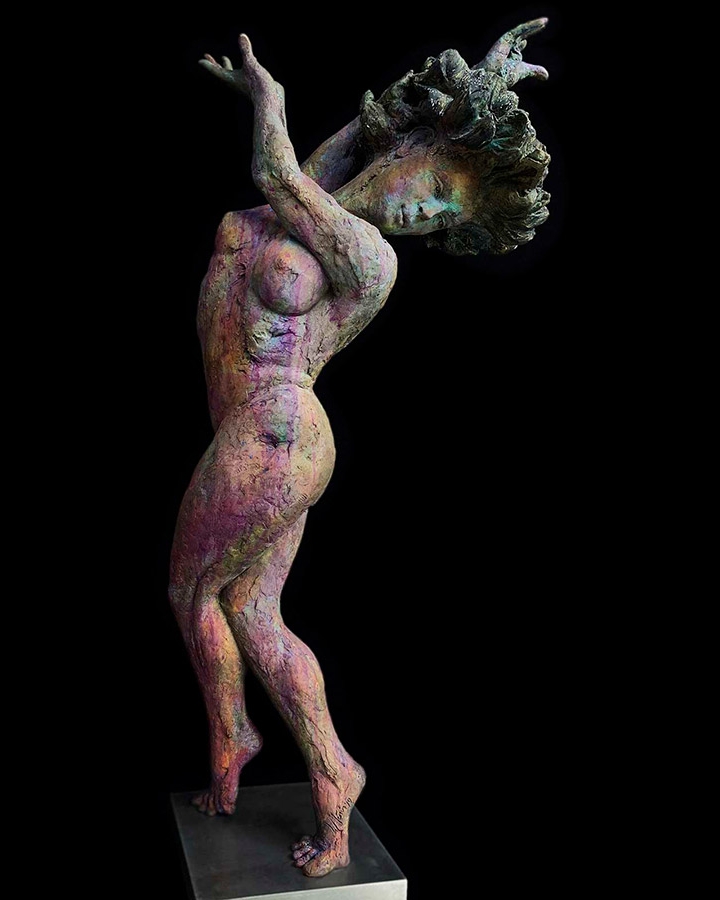

Written over the last 20 years of his life, Marcel Proust reflected on the pages of In Search of Lost Time about the meaning of existence and concluded that only pain allows us to "develop the forces of the spirit." Each pain disfigures our face, "like those faces of old Rembrandt", but pain is a force that can be transformed into another, "let us accept, then, the physical damage that it causes us in exchange for the spiritual knowledge that it brings us".

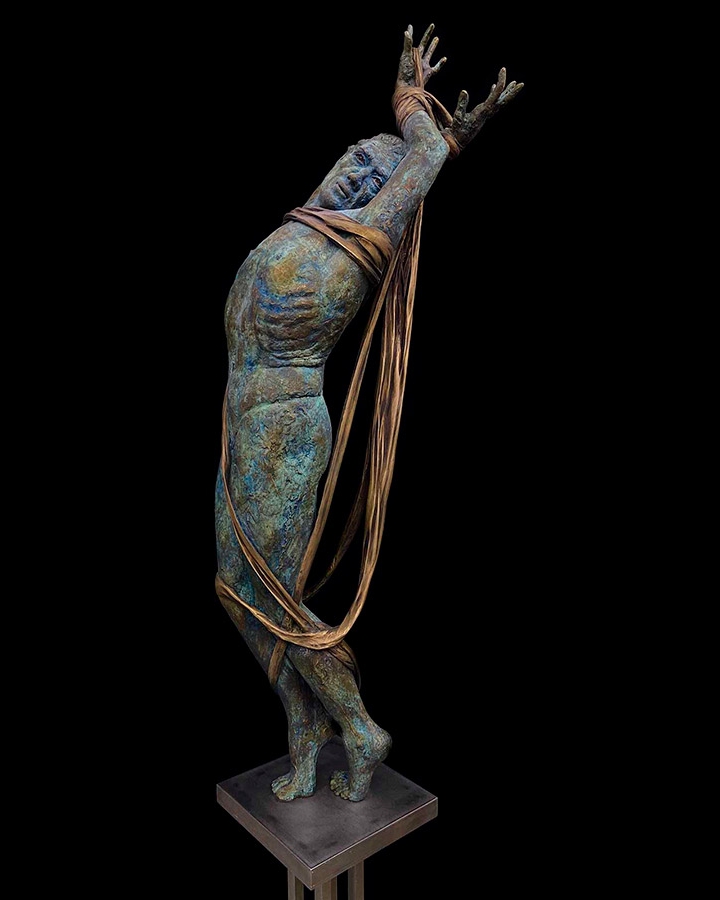

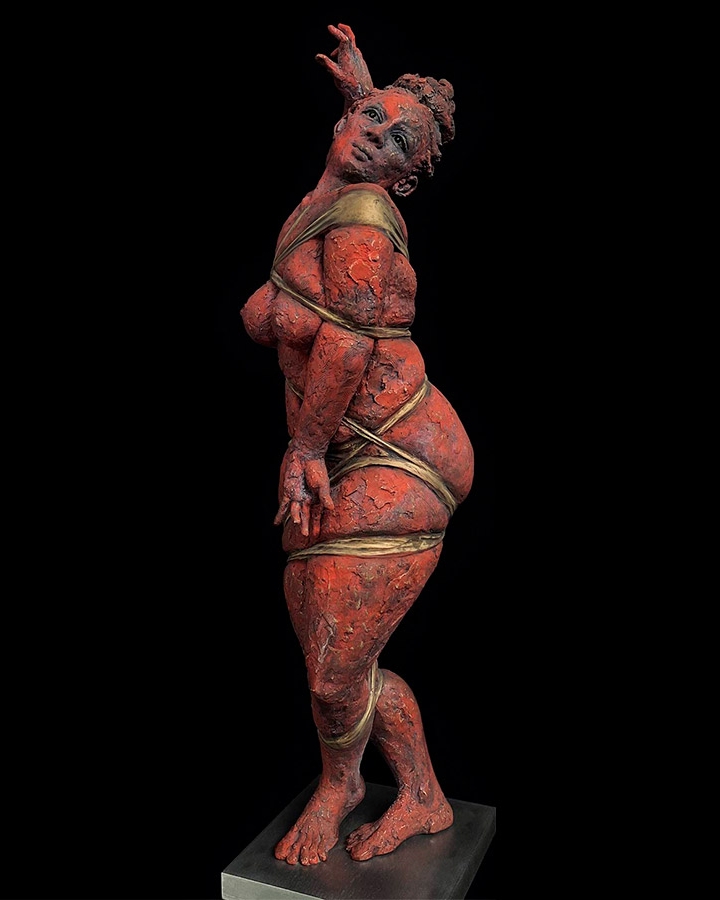

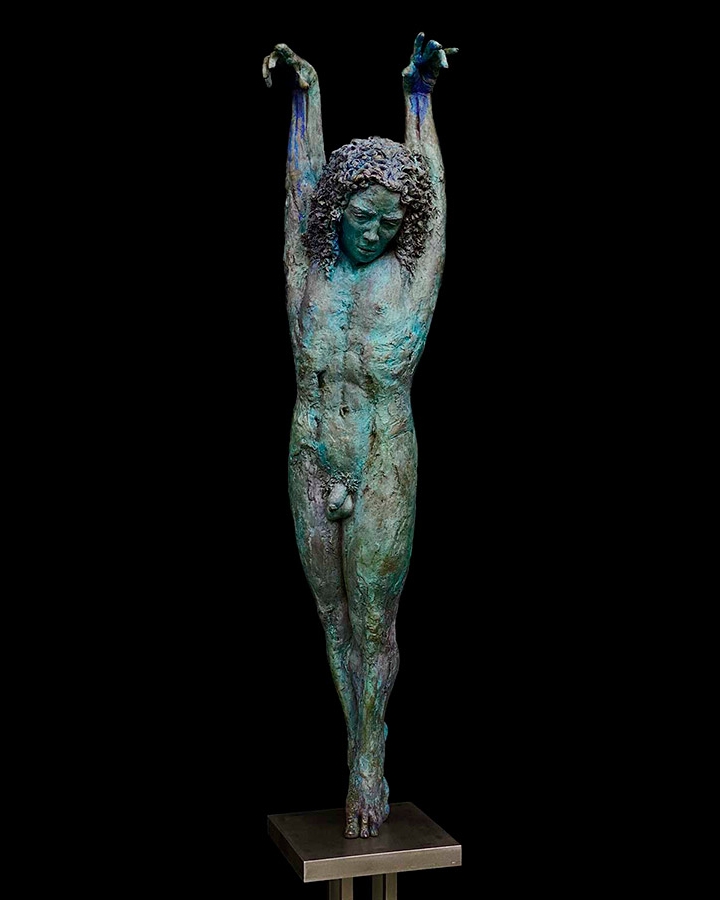

But how to carry out this transformation from one force to another, from pain to knowledge? The ten bronze pieces that make up the most recent exhibition by Walter Marín, Cicatrices, are shown as a kind of stages along the same path, that of self-knowledge. His pieces have hallucinatory, phantasmagorical and delusional characteristics, they seem to be about to issue an oracle that is better kept to avoid scaring us any more. His characters come from a forgotten, destroyed world, but where one last gesture is still possible, a dance step, the tense dance of the butō, whose movements seem to suggest that what has been lived is useless if it is not transformed into pathos; that is, if it is not made of that, the network of individual acts and random circumstances, an event, a symbol that offers meaning to our existence.

It's not an easy thing. These ten pieces not only seek the admiration of the viewer, they seek to inspire a state of consciousness, a field of resonance where it is possible to contemplate our own scars. They are not easy pieces to see (and much less to forget), they are a battlefield where the viewer cannot get away unscathed or unscathed. That is the true strength of art, therein lies its importance: in hurting us through beauty. That bond that binds and unties the characters in Cicatrices, that bond that sometimes tortures them and other times adorns and protects them, is nothing other than the risk of art, the sacred horror, the transforming fire that exists to disturb the world. order, as Plato well knew, who considered artists a danger. That danger, that threat that one faces when looking into the eyes of one of these characters, is to become one's own scar.

Walter Marín's pieces are a kind of optical instrument that he offers to the viewer and allows him to discern what, without the help of those pieces, he would not have been able to see himself. They are not a mirror, they are a scalpel. A pain to which Marín submits us, but for which we must be grateful: after seeing his pieces, we can get closer to what, sometimes familiarity and other times ignorance, makes us call "I"..